Design strategies: Design for all (Universal design, UD)

The combination of various trends in the society like aging, disability prevalence, increased expectations among workers and consumers with and without impairments resulted in an elevated need to have more inclusive design to accommodate across the full spectrum of human abilities. Increased dependence of automation had contributed to this as well.

The concept of universal design has rapidly evolved around the concept that tasks and other life activities should be easy and comfortable for all people with diverse features. This concept is also well applied in designing workplaces as workplaces become more and more diverse. Inclusive design or universal design (UD) is one of the few user-centred design paradigms that advocate consideration for the full spectrum of human abilities, including individuals with and without disabilities.

As older adults and individuals with disabilities have become more independent and actively participating in employment, educational and recreational opportunities expectations for safe, accessible and equitable products and environments have increased. Enforcement of federal accessibility legislations in many countries has also been instrumental in advancing the rights of vulnerable user populations. Furthermore, complex technologies (e.g., automation, virtual interactions) have now become omnipresent in everyday lives which includes employment, education, healthcare, recreation to name a few.

Universal Design (UD) and HFE

Human factors and Ergonomics (HFE or E/HF) practitioners play a significant role in ensuring the components of UD are included in the design solution to address the human abilities. HFE practitioners are responsible to quantitatively evaluate artifacts and solutions to engineering design problems for human use, including for people with diverse impairments. Some examples like domains of transportation (e.g., older drivers, driverless and autonomous vehicles), healthcare (e.g., home-based care, medical device design, and patient safety devices) and occupational settings (e.g., aging workforce issues, obesity and functional work capacity) (D’Souza 2017)

Universal Design (UD) concept

The concept of universal design emerged from barrier free design, which took into account the needs of people with disabilities (Welch 1995). The idea of design for all existed for quite some time however the idea received attention only after the Center for universal design at the State university of North Carolina issued the principles of Universal Design. It was even more evident with the passing of the American Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990. Although the rights of people with disabilities are acknowledged the consideration must involve other groups whose needs differ from those with disabilities (Kose 2006). It is still evolving in different part of the world. The focus is towards addressing the diverse needs of a wide variety of individuals in designing infrastructure, buildings, and consumer products.

Many European Union Member States have inclusive design legislation, which is relevant both nationally and internationally. Key policies include human rights and equality, rights of disabled persons, social inclusion, and sustainable development. The EU Accessibility Act (EU Directive 2019/882) applies to products and services from 2025 and provides an umbrella to encourage participation of differently abled people as it secures accessibility of public sectors and is relevant for the design of working environment. In countries like Germany, barrier-free building and public zone design should refer to national standardisation (e.g. DIN series 18040:2014), however, national legislation and regulation apply to the design of working places (ASR V3a.2:2022; see also DGUV Information 215-111/112). In the USA more advancement happened with Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines (1991), and Americans with Disabilities Act/Architectural Barriers Act Guidelines (2004). On the other hand, the legislations in Canada such as Employment Equity Act (section 2), Canadian Labour Code (Part II, Occupational Health and Safety, sections 124 and 125), and the Canadian Human Rights Act (Part I, section 3(1)) have addresses employer responsibilities, health and safety at work, and worker discrimination, respectively. In a most recent development on December 13, 2021, the Accessible Canada Regulations, SOR/2021-241 (the “Regulations”) came into force. Under these Regulations federally regulated employers became obligated under the Accessible Canada Act, to prepare and publish accessibility plans, descriptions of feedback processes, and progress reports. The Regulations also establish monetary penalties to promote compliance with the Act (ESD Canada 2021 for Guidance on the Accessible Canada Regulations).

In Japan the Law for Building Accessibility (the Heartful Building Law) has made terms like "barrier-free design/ accessibility" and "universal design" more common (JEED 2022). Manufacturers and advertising agencies have built a new marketing strategy that even helped businesses recover from their long recession in the country. As a result, new amendments are being made to the Heartful Building Law due to the popular demand (Saito 2006). On top of that the Occupational Safety and Health Act laid the ground rules in hiring older workers for the following criteria: work management, work environment, workers' health, overall management, and safety education (Jeong & Shin 2014).

Universal Design (UD) definition:

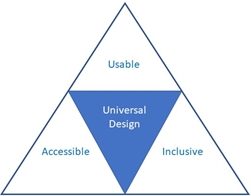

According to the Center for Universal Design (1997), UD is “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design” (see Figure 1). To make it specific it could be replicated based on the sectors. For example, to apply UD in workplace design “the design of product, system and environments to be usable by all people”.

Universal Design (UD) framework:

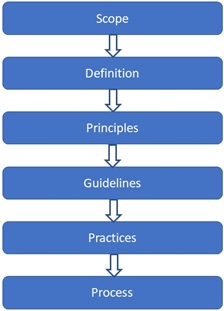

Like any other design framework (see Figure 2), the basics UD framework starts with the scope of work and application areas, Definition of the problem, then following the principles, guidelines and finally focuses in to practise and processes.

Universal design (UD) principles and its application in worksystem design

Initially Universal design terms was commonly used for product design, architecture and interior design. As the spaces become more inclusive the term needs to be redefined for workplace design. Based on the 7 basic principles of universal design (Center for Universal Design, 1997), the following design elements to be considered in workplace design (Jeong & Shin 2014) (see Table 1).

Table 1: Work system design elements (Jeong & Shin 2014) to be considered referring to 7 basic principles of universal design (Center for Universal Design, 1997).

| UD Principles | Design Elements |

|---|---|

| 1. Equitable use |

|

| 2. Flexibility in use |

|

| 3. Simple and intuitive use |

|

| 4. Perceptible information |

|

| 5. Tolerance for error |

|

| 6. Low physical effort |

|

| 7. Size and space for approach and use |

|

Universal Design (UD) examples of general issues to be addressed in designing work systems

(1) Universal Design (UD) of workspace

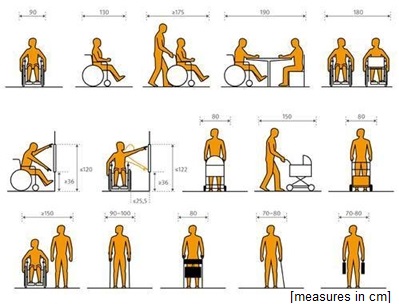

Design issues presented are relevant for a broad range of user, probably, but not limited to older adults, differently abled, short term disabled: injured, pregnant and so on.

Design Considerations (Space):

- Walkways and aisles to provide access to machines or to move around machines

- Wider doorways, assisted ingress and egress (automation)

- Facilities like restrooms, lunchrooms, offices, board rooms also to be accessible

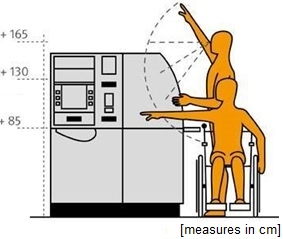

Example: Wheelchair users do need wider space. Sometimes this is not included in design if it is not for all / not accessible. (see Figure 3).

(2) Universal Design (UD) of arrangement and location of displays and controls

- Reachability for differently abled

- Special provision for clearance

- Special allocation of displays and controls

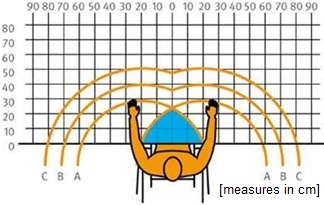

Example: Wheelchair users need to control machine (displays and controls need to be in area of reach, i.e. adjustable for height or sets of displays and controls at different locations) (see Figures 4 and 5).

(3) Universal Design (UD) for human information processing

- Sensory consideration (like auditory impairment, colour blindness)

- Response time

- Flexibility in use

- Simple and intuitive use

- Error tolerance

- Perceptible information design

- Task and feedback design

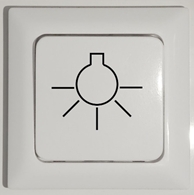

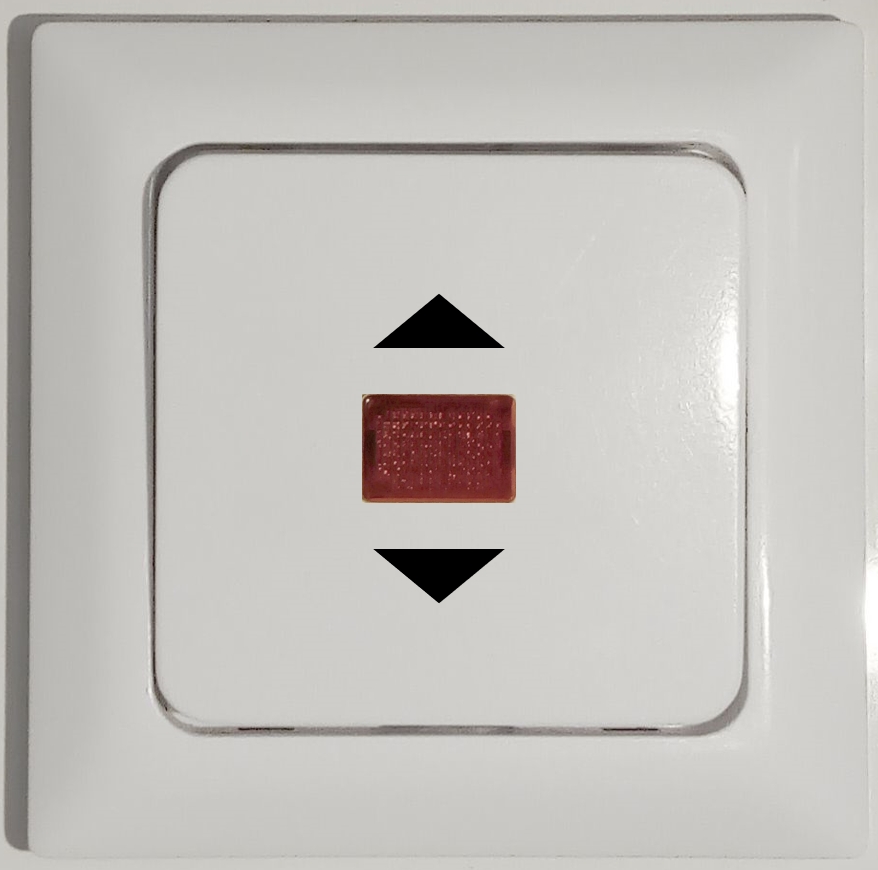

Examples: Sensual impairments (e.g. visual, haptic, auditory) require signalisation for multiple-sensory systems, displays for human-system interaction should provide clear contrasts, for operating areas, for form of controls (see Figures 6, 7 and 8, see also DGUV Information 215-112 2017).

References

- Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (2017). [https://www.ada.gov]

- Burgstahler S. (2021). Universal Design: Process, Principles, and Applications How to apply universal design to any product or environment. Seattle: University of Washington, DO‑IT.

[https://www.washington.edu/doit/universal-design-process-principles-and-applications] - Center for Universal Design (1997). The principles of universal design (Version 2.0 - 4/1/97). Raleigh: North Carolina State University (USA). [ https://design.ncsu.edu/research/center-for-universal-design/]

- D’Souza, C. (2017), Topics in inclusive design for the graduate human factors engineering curriculum, Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 61(1), 403-406. [https://doi.org/10.1177/1541931213601583]

- DGUV Information 215-111 (2015). Barrierefreie Arbeitsgestaltung. Teil 1: Grundlagen [Design of working conditions for accessability. Part 1: Basics]. Berlin: DGUV.

- DGUV Information 215-112 (2017). Barrierefreie Arbeitsgestaltung. Teil 2: Grundsätzliche Anforderungen [Design of working conditions for accessability. Part 2: General requirements]. Berlin: DGUV.

- DIN series 18040 (2014). Barrierefreies Bauen - Planungsgrundlagen - Teil 1: Öffentlich zugängliche Gebäude, Teil 2: Wohnungen, Teil 3: Öffentlicher Verkehrs- und Freiraum [Construction of accessible buildings - Design principles - Part 1: Publicly accessible buildings, Part 2: Dwellings, Part 3: Public circulation areas and open spaces]. Berlin: Beuth.

- EU Accessibility Act (2019). Directive (EU) 2019/882 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on the accessibility requirements for products and services. Official Journal of the European Union (7.6.2019), L 151/70. [http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/882/oj]

- ESD Canada (2021). Guidance on the Accessible Canada Regulations - Module 1: Accessibility Plans. Employment and Social Development Canada.

[https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/accessible-canada-regulations-guidance/accessibility-plans.html] - Jeong B. Y. & Shin D. S. (2014) Workplace Universal Design for the Older Worker: Current Issues and Future Directions. J Ergon Soc Korea 33(5), 365-376.

- JEED (2022). About JEED (Japan Organization for Employment of the Elderly and Persons with Disabilities and Job Seekers), retrieved Aug 2022

[https://www.jeed.go.jp/english/about_jeed/index.html] - Kose S. (2006). Universal Design for the Aging. In W. Karwowski (Ed.), International Encyclopaedia of Ergonomics and Human Factors (pp.227-230). New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Saito, Y. (2006). Awareness of universal design among facility managers in Japan and the United States. Automation in Construction 15(4), 462-478. [https://doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2005.06.013]

- Welch, P. (1995). Strategies for Teaching Universal Design. Boston: Adaptive Environments Center.

Back to "The Strategies of Work System Design"